Unstructured Data in 2026

I’ve written a lot of articles on unstructured data since the rise of GenAI and I thought it would be interesting to look at what we can expect for unstructured data in the enterprise in 2026.

For years, unstructured data has been treated as an unavoidable liability. Companies stored it cheaply, searched it poorly, and hoped they didn’t have to touch most of it. The LLM wave changed that, but not because it solved unstructured data, but because it exposed how much potential value might be locked inside documents, conversations, media, and logs.

By 2026, unstructured data does become more operational, but it does not become cheap, simple, or safe to process indiscriminately.

Large organizations will still struggle to “process everything,” and will accept hard constraints (scale, cost etc) and design for them explicitly.

The Category Still Collapses (but the physics don’t)

In 2026 documents, emails, transcripts, images, videos etc increasingly sit alongside transactional data as legitimate inputs to analytics, automation, and decision-making. The question is no longer whether unstructured data matters, but how much of it you can afford to understand, and under what controls.

The idea that all unstructured data becomes continuously understood is directionally correct but at petabyte scale, the physics assert themselves. Compute, I/O, and data movement costs dominate. Reading the data is often more expensive than storing it. Reprocessing it repeatedly, from a cost and process perspective, is not viable.

So while the distinction between structured and unstructured data erodes at the information layer, it persists very stubbornly at the economic and governance layers.

Why “Process Everything” Breaks At Enterprise Scale

One of the most dangerous narratives entering 2026 is that falling model costs make “process everything” inevitable. They don’t.

At PB scale:

Inference costs compound into seven-figure annual run rates.

Network egress and object-store reads exceed model spend.

Backlogs become permanent; latency becomes a business issue.

Operational failure modes look more like industrial systems than data pipelines.

The practical response is not universal processing, but tiered understanding.

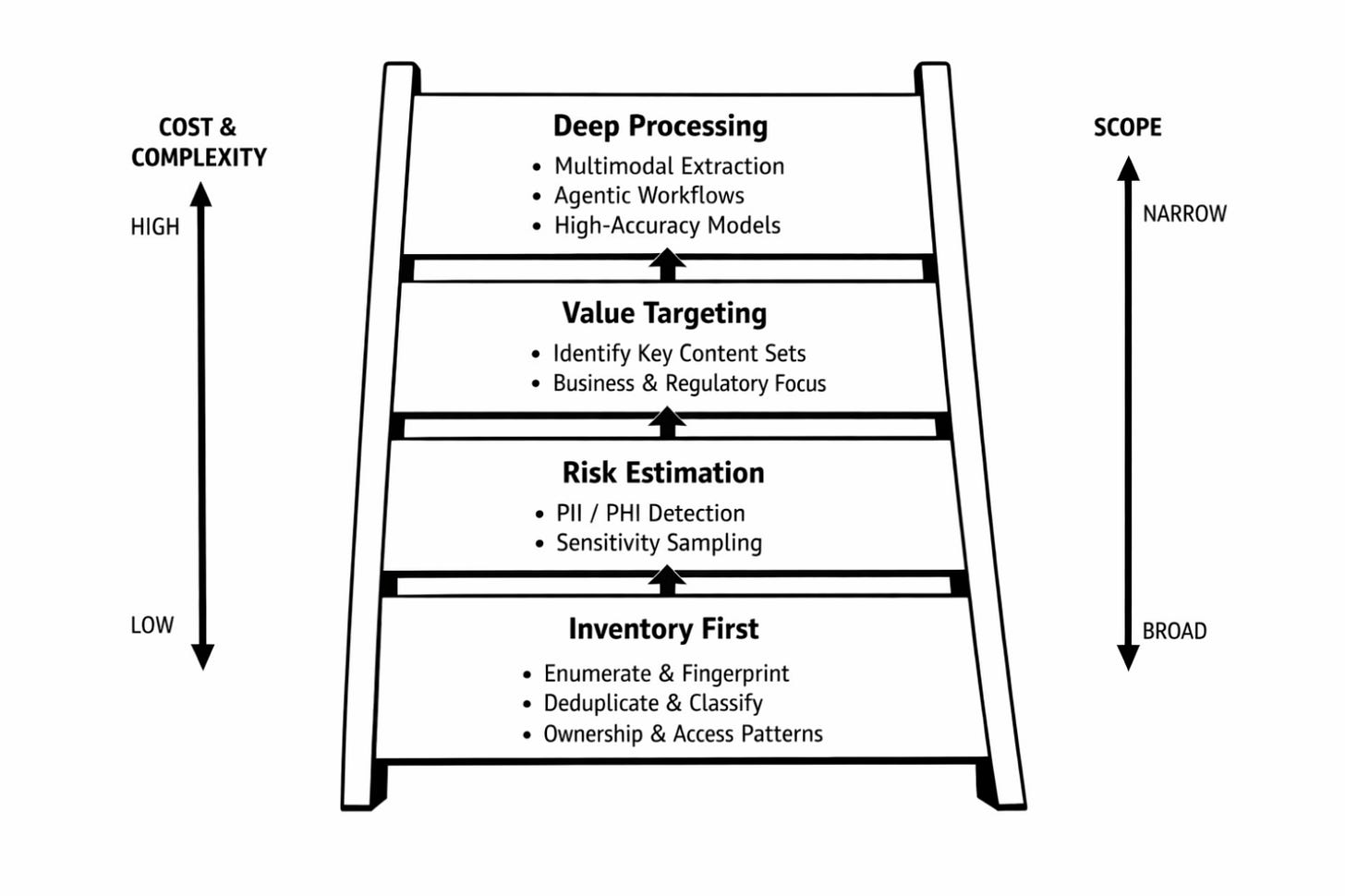

I think we will see successful architectures follow a laddered approach:

Inventory-first: enumerate, fingerprint, deduplicate, establish ownership, age, access patterns.

Risk estimation: lightweight PII/PHI detection, sampling-based sensitivity estimation.

Value targeting: identify collections of content with clear business use cases and/or regulatory payoff.

Deep processing on demand: multimodal extraction, agentic workflows, high-accuracy models (used selectively)

This replaces the corporate fantasy of full understanding with measurable distributions of risk and value across an otherwise unknowable (dark) data estate.

Processing The Unknown Is The Real Cost Center

The most expensive moment in any unstructured data program is not extracting known entities from known document types. It’s the first pass over content you cannot describe.

“What’s in these file shares?” “Which backups contain regulated data?” “How much of this content even matters?”

Every organization underestimates this phase and many end up stalling here.

I believe we need to stop pretending this is a one-time discovery exercise. Treat “unknown unknowns” as a standing condition, and design systems that progressively reduce uncertainty rather than eliminate it.

This is why organizations keep the original files as the source of truth, and treat AI outputs as temporary results that can be regenerated or discarded.

Retrieval in 2026: Hybrid by Default, Use-Case and Risk Driven

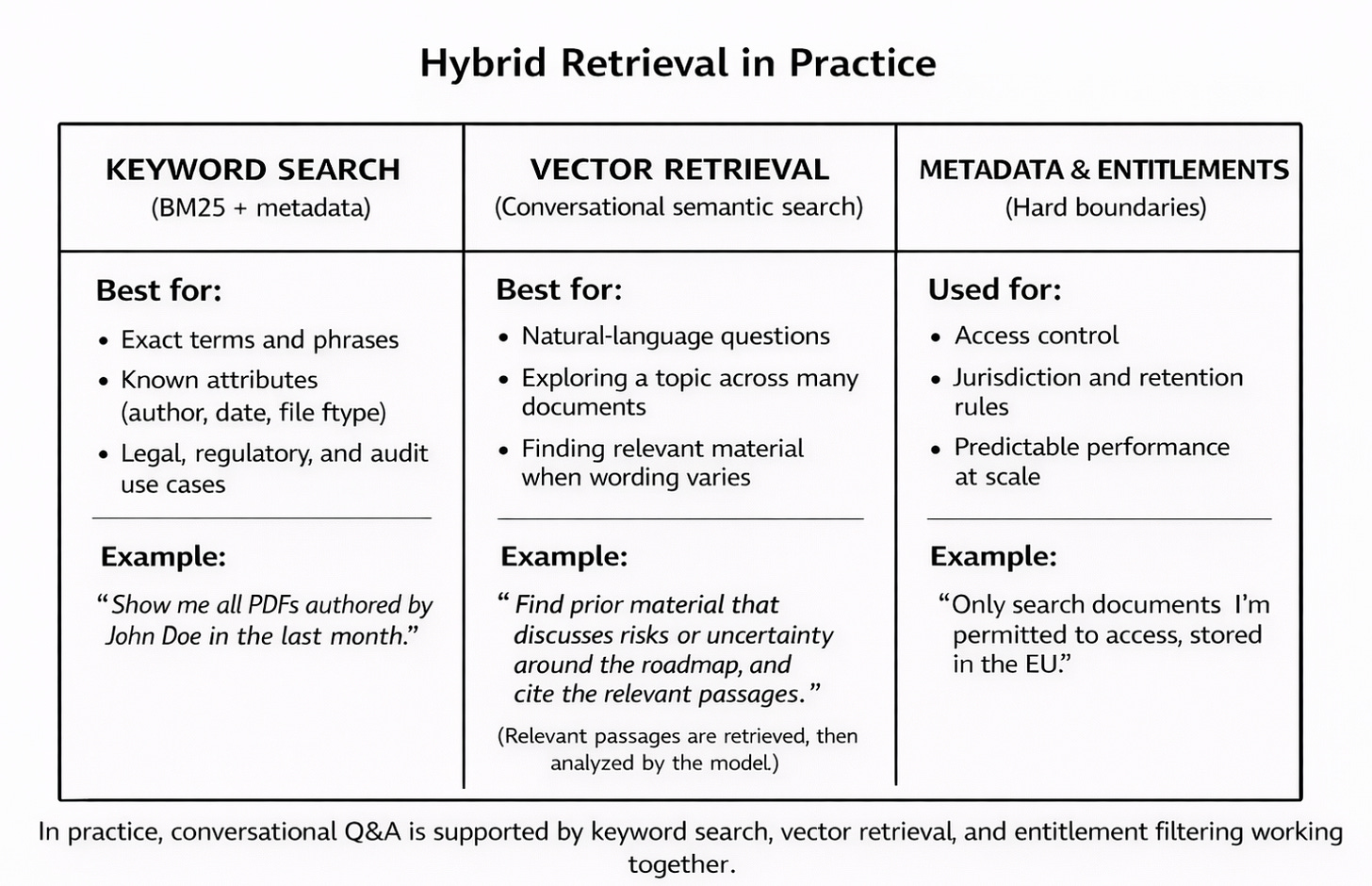

By 2026, retrieval is no longer a single technique or architectural choice. Successful systems assume from the outset that different retrieval methods solve different problems, and they combine them deliberately based on the use case, the required precision, and the risk of being wrong.

No single approach replaces the others.

Keyword Search (BM25 And Similar)

Keyword search remains essential where explicit constraints and exact matches matter.

It excels at:

precise term and phrase lookup

queries driven by known attributes (author, date, file type)

legal, regulatory, and audit scenarios where wording matters

explainability and deterministic behaviour

Example:

“Show me all PDFs authored by John Doe in the last month.”

This is a straightforward keyword and metadata query. Vector similarity adds no value here and can actively reduce precision. When the user knows exactly what they want to constrain, keyword search is still the right tool.

Another example:

“Find contracts containing the phrase ‘termination for convenience’.”

Exact wording is the requirement, not semantic similarity.

Vector Retrieval (Semantic Similarity)

Vector retrieval is best understood as conversational question-and-answer over large collections of content. Instead of specifying exact keywords, people describe what they’re trying to find in natural language, and the system retrieves relevant passages that the model can then read, reason over, and cite.

It works well when:

the user knows the topic or question, not the exact wording

the same idea appears across many documents in different language

the task is exploratory, analytical, or investigative

It is not about applying logical filters or deciding what qualifies. Its role is to retrieve candidate content that is semantically related to a described intent, even when the language varies.

It is useful for:

semantic narrowing across large, diverse content sets

surfacing related material when exact terms are unknown

exploratory discovery

Example (semantic retrieval + synthesis):

“I’m writing a report. Please find prior material that expresses uncertainty or disagreement about the roadmap, and outline each instance with citations.”

In this case:

vector retrieval is used to surface passages that are about uncertainty, risk, pushback, or concern (even if those words never appear)

an LLM then reads those retrieved passages, identifies relevant instances, and produces the cited outline

The key point is that vector retrieval selects candidates; it does not make final judgments. Reasoning, extraction, and citation happen after retrieval.

Metadata And Entitlement Filtering

Metadata and entitlement controls act as a pre-filter, not a search method.They determine which documents are eligible to be searched at all, based on access rights, jurisdiction, retention rules, and policy constraints. Keyword search, vector retrieval, and conversational Q&A all operate inside this permitted set. If content fails an entitlement check, it is excluded before any semantic or generative processing occurs.

They provide:

strict access controls

jurisdictional and retention enforcement

predictable performance at scale

Example:

“Only search documents I am permitted to access, stored in the EU, and governed by the customer-support retention policy.”

These constraints must be applied before any keyword or vector retrieval occurs. No semantic relevance can justify violating access rules or regulatory boundaries.

How This Comes Together in Practice

In real systems, these techniques are combined rather than chosen in isolation.

A common pattern looks like:

Metadata and entitlement filtering to establish what can be searched

Keyword search to enforce precision and explicit constraints

Vector retrieval to surface semantically related candidates

RAG and/or CAG, long-context reasoning to synthesise answers or extract evidence

In 2026 it is best to assume retrieval will always be imperfect, particularly at scale. Instead of stacking complexity to “fix” it, system architects should evaluate:

use multiple retrieval methods together

vary strategy by use case (search, analysis, compliance, reporting)

make trade-offs between precision, cost, latency, and confidence explicit

The question is no longer “Are we using Keyword Search or vector search?” It becomes “Which combination of retrieval methods is appropriate for this use case?”

Governance Gets Harder, Not Easier

The optimistic would says governance improves because models auto-classify content accurately enough to trust.

I think the 2026 reality is a little harsher. Classification accuracy improves, but trust is not a statistical threshold - it’s a legal and operational one. “The model was 96% confident” does not work in an enterprise setting, or survive an audit, a breach, or a courtroom.

As a result, governance shifts focus:

from tagging to provable lineage

from policy intent to enforcement evidence

from perfect accuracy to defensible controls

Provenance becomes mandatory. Every extracted field, summary, and AI-generated artifact must be traceable to its source, transformation steps, and model version. This matters not just for compliance, but for epistemology i.e. knowing whether you are looking at primary content, derived interpretation, or synthetic synthesis. pasted

Regulations, Not Technology, Sets The Ceiling

Regulation is increasingly determines what architectures are viable. Existing requirements are already exerting some pressure:

Data minimisation clashes with “process everything” strategies.

Right-to-deletion collides with backup-heavy unstructured estates.

Cross-border processing rules complicate cloud-only approaches.

Litigation holds expose the fragility of continuously rewritten interpretations.

By 2026, the “everything goes to a single LLM API” pattern is no longer defensible for many organizations. Heterogeneous processing - local models, in-VPC inference, redaction layers, selective cloud use are likely to become standard. Not necessarily because it’s elegant, but because it’s survivable.

Agents Replace Glue Code (Within Limits)

Agent-based workflows do become the dominant way of operationalizing unstructured data - but not as autonomous actors.

Their real value is pragmatic:

handling variability

executing multi-step interpretation

escalating ambiguity

bridging fuzzy outputs into structured systems

They succeed where prior rule-based automation failed, not because they are smarter, but because they accept inconsistency as normal. Still, by 2026, agents will end up operating inside tightly constrained envelopes (scoped permissions, logged actions, human checkpoints) for high-risk decisions.

The Real 2026 Change

The biggest change is not technical it’s more cultural and it has been building up over the last few years.

Unstructured data is starting to stop being treated as a compliance burden or a curiosity. It is becoming a primary information source, but one that is expensive, probabilistic, and legally constrained.

There are three core truths around unstructured data that I believe will still hold true in 2026:

At large enterprise scale, you may never fully understand all your unstructured data.

Processing everything is usually the wrong goal.

Governance must be designed for evidence, not aspiration.

The distinction between structured and unstructured data fades. The distinction between controlled understanding and reckless processing becomes decisive.

That is where unstructured data is actually heading - toward disciplined, selective, auditable intelligence at scale.